Protecting the purpose-driven culture you are building

Most of what has been covered in the Purpose-Driven Culture Series has focused on how to create frameworks and tools that enable you to efficiently and effectively support individual development and to cultivate the type of employee engagement that will propel your company towards success. However, there will be times when it is necessary to manage people out of your organization or risk jeopardizing the health of the engine that fuels your company’s results: your purpose-driven culture.

Whereas the previous article on delivering effective performance feedback includes how to accurately assess chronic underperformers, this article provides insights and techniques for how to exit those who are not the right fit for your organization. Balancing the need to protect the culture you are building with a respectful termination process for underperforming employees can be a tricky path to navigate and comes with some very real employment law considerations. Nonetheless, you can still handle these situations effectively with thoughtfulness and sensitivity.

While there is no single “right way” of managing an employment termination process, there are plenty of potential pitfalls of which one should be aware. To be clear, I am neither a human resources professional nor an employment law expert, but I have led my fair share of complex, harrowing employment termination scenarios. None of the content of this article should be construed as constituting formal HR/legal advice. As an executive, who has had oversight of companies and teams, and as a direct supervisor, who has managed this process first-hand, my intent in sharing these lessons and tips is:

- to provide a comprehensive view of more common considerations when managing the challenges of exiting an employee

- to sensitize leaders to when it may be time to engage a human resources (HR) or employment law professional or other relevant experts

- to outline what steps you can take to manage these situations with as much respect as possible for all impacted parties

As you adopt and integrate the practices covered in the other articles in this series, the frequency of needing to exit underperformers will diminish over time. Avoiding these tough situations when they do arise will damage your purpose-driven culture and jeopardize your company’s success. Depending on the style and risk tolerance of your organization, there will likely be some aspects of this article that will seem unnecessary. With that in mind, I have erred on the side of providing a broader array of considerations to spark ideas for leaders on how to curate and create a right-fit process for your organization.

A Quick Recap of Purpose-Driven Culture and Why It’s Important

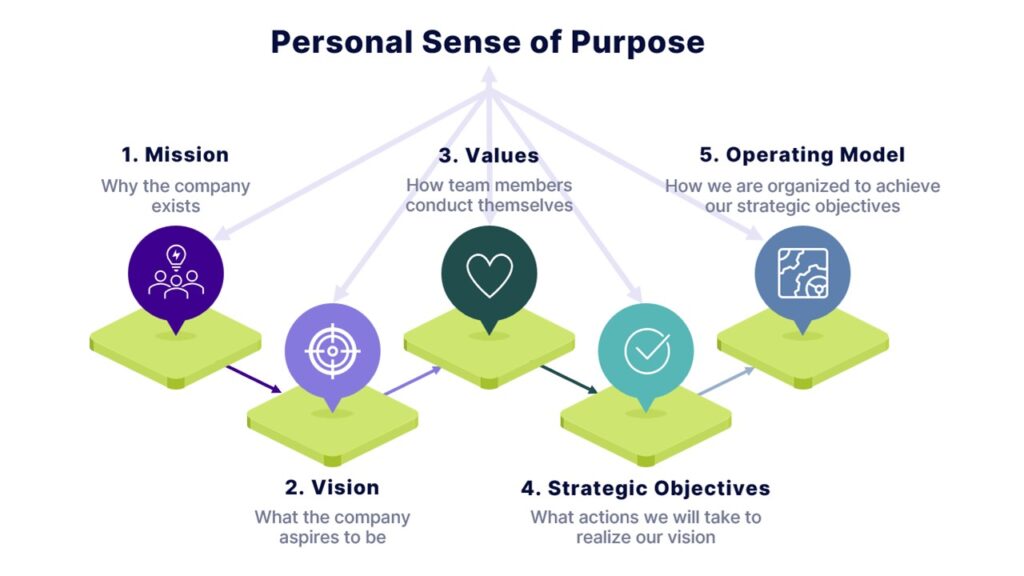

As noted in previous EverSparq articles, purpose-driven culture promotes connection, high engagement, and meaningful productivity gains by making work resonate on a personal level. (In the EverSparq article Connecting to Purpose: Creating a Purpose-Driven Culture, I outlined the Purpose-Driven Strategic Framework (Figure 1) and provided 5 tips for how to connect employees’ personal sense of purpose to the specific elements of the framework to support a purpose-driven culture.)

We may not always realize it but there is almost always something deep within each of us that motivates and drives us even during the most challenging times. Our true North. Helping individuals identify what that is and then determining how that applies in their daily work creates a level of meaning that is incredibly profound. This increases a personal sense of ownership and accountability for the success of the company and manifests in ways such as higher productivity, better quality work, and achievement of goals that, when aligned properly using the Purpose-Driven Strategic Framework, can propel companies forward in successful strategy execution.

In the Purpose-Driven Culture Series article, Delivering Effective Feedback, I reviewed techniques for recognizing and attempting to get to the root core of why an employee is underperforming. In this article, the focus is shifting to those who have now progressed to the level of needing to be exited from the company.

The practical reality is that part of building a purpose-driven culture is the recognition that not everyone thrives in or is able to embrace what it takes to be a part of a high-performing, purpose-driven organization. That does not necessarily mean they are a bad person or somehow defective, it just means they are not the right fit for your company culture and your company culture may not be a good fit for them.

Learning to recognize when an employee is at risk, taking steps to do what you can to support them on getting back on track, and being willing to lean into the tough conversation of exiting someone from the organization when it becomes apparent that, despite best efforts, there is no longer a good fit is critically important for protecting your purpose-driven culture.

The Hallmarks of When It’s Time to Say Farewell

Sometimes accepting that an employee is no longer a good fit for your organization may feel like a failure to the employee and you as the supervisor. Or the supervisor believes that by being passive, they are exhibiting compassion. Neither are good reasons to delay taking appropriate action. The respectful thing to do is to clear the way for the individual to find somewhere where they can be successful and to remove the unproductive friction that is adversely impacting your other employees. Reframing your thinking to recognize that you are not doing the employee any favors by doing nothing and continuing to allow them to be set up for failure can create a more productive context for you to make the tough call that it is time to part ways.

Though this is by no means an exhaustive list, here are some more common, typical signs that an employee is not a fit for your company:

1. Minimal Progress Despite Clear Expectations

Referring to the recent EverSparq article on providing effective feedback, using the SBI (situation, behavior, impact) feedback framework is a reliable way to ensure that you have clearly delineated the performance issue(s) and made your expectations of what must occur for the employee to improve. More on this later when we cover the Performance Improvement Plan (PIP).

2. High Recidivism

One way that poor fit employees last so long in an organization is that they improve temporarily only to repeatedly backslide into underperformance. This can be especially challenging to identify if the employee has migrated between supervisors, in which case it becomes increasingly likely that no single supervisor will be fully aware of the comprehensive track record of underperformance. Said differently, whereas a single incident may be cause for a warning, a pattern of repeated incidents that would lead you to potentially manage someone out of the organization is easier to miss.

3. Unable to Adapt and Keep Pace with Evolving Company Needs

Depending on the industry, the pace of change, whether that is due to shifting market dynamics, company growth, or other factors, may be fast enough that certain individuals cannot or do not want to keep up despite ample support and attempts to develop agility and adaptability. This typically manifests as the individual who is unwilling to change, often opining that “this is how we’ve always done it”. This creates a drag on the rest of the team and compromises the ability of the company to respond effectively to the need to evolve and remain relevant.

4. Support and Resource Options Have Been Exhausted

Out of respect for the individual, I like to make sure I was clear in my expectations and as supportive as I reasonably could be before taking steps to exiting an employee. However, there comes a time when no amount of additional mentorship, training, and resources can help someone improve to meet the expectations of their role.

5. Employee Flouts Purpose-Driven Culture Expectations

This may seem obvious, but I am amazed at how often supervisors tolerate florid insubordination and frank disrespect. It is true that everyone has a bad day but a consistent behavioral track record that indicates someone thinks they are above the rules and expectations of the company is a likely sign that this person is not a fit. (However, this type of behavior may be an indicator that something may be off with the company expectations or practices that should be reviewed as appropriate before taking disciplinary action.)

Zero-Tolerance Behaviors

In addition to these common signals, be clear and up front with employees about your company’s zero-tolerance behaviors. This may include but not be limited to racist or other discriminatory behaviors, physical or psychological violence, or fraudulent actions. These expectations and the consequences, including potential termination of employment, should be clearly documented in employee handbooks and any relevant policies and procedures.

Then, act consistently according to these requirements. Suboptimal responses to zero-tolerance infractions such as letting the employee off the hook with a warning sends a mixed and confusing message to the entire company. Not only is there a risk that the employee may offend again later, the lack of consistent follow-through for meting out accountability promotes a culture of optionality where expectations and the things that constitute purpose-driven culture are just rhetoric and not really taken seriously within the organization. This is incredibly corrosive to a purpose-driven culture.

Preparing to Exit an Employee

Again, while not an employment law expert or HR professional, there are some steps I have learned from these types of colleagues that I know will create clarity more expediently and reduce the risk of a disrespectful process if you anticipate and prepare in advance:

1. Involve the Necessary Support Resources & Expertise

As noted previously, exiting an employee may create potential exposure to civil action. Involve experts to help you navigate the process in a manner that minimizes that risk. Ideally, if you are proceeding down this path, you would involve experts like a human resources (HR) professional well-versed in HR best practices and risk-related considerations. They will help you make sure you are documenting appropriately and help you determine whether additional support is required such as an employment attorney. The size of your company and associated corporate services as well as your risk tolerance will determine when and how to access these types of resources.

2. Keep a File & Document Events

This might seem like overkill until you need it. Most documentation should reside in a confidential employee file. Rather than scrambling to assemble documentation related to your decision to exit an employee, tracking as you go helps you limit your and your organization’s legal exposure to potential civil action. It also helps maintain a longitudinal record of the employee’s performance that will follow them as they transition from one supervisor to the next, minimizing the risk noted earlier of missing a pattern of repeated underperformance.

When documenting events, use objective and non-emotional language. Just the facts. Avoid interpretative rhetoric or judgmental commentary.

So what kind of documentation is relevant? Here are some common examples:

- Performance Reviews & Improvement Plans

These should contain clear documentation of performance concerns and remediation plans. Having both the supervisor’s and the employee’s signature acknowledging that the feedback has been shared (obtained at the completion of the performance review) leaves little room for doubt that clear expectations have been discussed. - Examples of Specific Situations

While the annual review summarizes the preceding 12-month period, one should not wait that long to share performance concerns. Events should be addressed and appropriately documented in a timely manner, otherwise you risk creating a performance management culture that I call the “4 F’s of Performance”: “you’re fine, you’re fine, you’re fine, you’re fired.” Rather than creating a purpose-driven culture that promotes a fair and equitable environment in which employees seek feedback to improve, this “gotcha” style of performance management promotes a punitive environment in which people perform based on fear of punishment and retaliation. An isolated situation may not seem worthy of documentation until a pattern of repeated offenses begins to emerge. Keeping track of these events, including the date of occurrence as well as when the concerns were reviewed with the employee, will help you distinguish between an isolated misstep versus a pattern for concern. - Substantiating Evidence

Ambiguity and conjecture are not compelling (or defensible) ways to build a case for employment termination. This leaves room for baseless accusations and unsubstantiated complaints that are neither fair to nor helpful for your employee and will leave you and your organization wide open to potential civil action. Provide the benefit of the doubt to the employee and validate that performance concerns are real and legitimate with as much evidence as is reasonable before jumping to a conclusion. This may take the form of emails or other documents, testimonials, information technology reports (e.g., unauthorized access to IT systems, etc.), or even video footage.

3. Complete a Performance Improvement Plan

In addition to employment termination due to violation of zero-tolerance performance expectations, there may be circumstances under which it may be appropriate to terminate someone’s employment abruptly. This could be due to early mutual agreement between the employee and the supervisor that things are no longer working out. This is a discussion for the supervisor to have with an HR professional and/or employment lawyer. Even if this turns out to be the preferred course of action, determine with your expert advisors what degree of supporting documentation may be necessary.

Otherwise, as a general practice and as noted earlier, the performance improvement plan (PIP) is an important document to have on file and it will serve as an important guide for your conversation with the employee when you meet to review your concerns and expectations. Here are some typical key components of a PIP for consideration:

- Performance Themes. Identify the key performance theme(s), e.g., lack of attention to detail, disruptive behavior, etc.

- Specific Examples. For each theme, provide no more than 2-3 examples. Typically, these should not come as a surprise to the employee since they ought to have been reviewed previously with them at the time of the event.

- SBI Format. The SBI outline can be a useful method for outlining the key points of the example:

Situation. a specific event or moment when the behavior was observed

Behavior. a brief description of the behavior(s) that was/were observed

Impact. a succinct outline of the impact you observed the behavior to have

- Clear Improvement Plan & Timeline. Clearly describe the improvement plan and expected outcome. The plan should be specific and time-bound with clear definitions for how it will be determined if the plan is successfully completed. This may be based on objective data and may include feedback solicited from specified individuals but there should be little if any room for doubt that the final arbiter of success is the supervisor.

- Follow-up Actions. This includes whether there will be any progress check-ins on the path to the deadline to review whether the employee successfully completed the plan. Sometimes, the employee needs time to process the discussion and may have follow-up questions. Anticipate this potential need and provide a reasonable period of time for questions and answers. But be clear that the clock is ticking as of the conclusion of the initial PIP discussion.

- Acknowledgement that the PIP Has Been Reviewed. If possible, much like the annual review, the formal PIP document will include a signature block for the employee to acknowledge that they have met with you on the date specified in the document. There may be occasions in which the employee refuses to sign the document because of a fear that they are somehow corroborating the documented concerns. Reminding them that the signature is an acknowledgement that the review has occurred rather than agreement with the findings can sometimes overcome this impediment. If they still refuse to sign, the best you can do is keep notes and, as will be noted later, always have a witness in the conversation, preferably an HR professional. While involving an attorney in this discussion may be an option, be aware that their presence will invariably heighten the anxiety and complexity of the interaction. Coordinate with your expert advisors on how best to notify the employee that others will be joining the meeting. For example, if an attorney is to be present, the employee may wish to have their own representation present (this process exceeds the scope of this article and should be coordinated with an HR professional or legal counsel).

4. Conduct the Termination Discussion

Once you have reached the point that it is time to exit the underperforming employee, the discussion should ideally be conducted in person or live with a third-party observer present like an HR professional. The conversation should be brief and to the point. Topics to cover may include:

- Termination date

- Any severance or pay-outs (e.g., accrued time off/sick leave hours, etc.)

- How you will handle requests for references; this should be discussed with your advising team as companies may have differing opinions on this matter. For some, the position of your organization may be limited to simple confirmation of a history of employment with your company and nothing more. In other circumstances, it may be deemed appropriate to provide a standard letter of reference.

- Expectations for how their departure will be communicated respectfully to others (e.g., colleagues, external contacts, etc.)

- Next steps for completing an offboarding checklist

- An HR point of contact for managing logistics and questions regarding such matters as COBRA and unemployment benefits, as appropriate

While meeting in person or live may seem like the most respectful approach, under certain circumstances, it may not be practical to meet in person (even by virtual means) or the employee may refuse to participate. In those situations, depending on the counsel of your advising team, a certified letter may be the best you can do. If conducted electronically, this should be done in a manner that confirms delivery and receipt of the letter.

As with the PIP, this can be an upsetting experience for the employee and they may attempt to bargain with you and negotiate. Be prepared to handle attempts to derail the conversation by redirecting back to the matter at hand with sensitivity. By this point, you have completed your due diligence and made a thoughtful decision that has been reviewed by your third-party advisors so spending time questioning yourself after the fact will not be a productive use of your time.

5. Complete Standard Offboarding Procedures

An offboarding checklist is just as important as one for onboarding employees. This is a standard checklist that you and your HR colleague will use to ensure that nothing critical has been missed in the process of exiting an employee. Examples of offboarding activities may include:

- Shutting off access for the individual to business systems and other platforms in a timely manner. This should be anticipated as you prepare for the steps leading up to termination of employment as certain positions and their associated access to certain information may present greater risk. For example, steps should be taken to prevent a disgruntled former employee who had access to highly confidential customer information from dispersing that data publicly.

- Collecting identification badges, keys, and equipment.

- Completing an exit interview, if deemed appropriate (typically conducted by an HR professional)

- Talking points for different audiences to address why the individual is no longer with the company. For external audiences, this should be general and brief. Internal messaging should be reviewed with the appropriate HR or legal advisor. This can be a delicate balance – you do not want to share anything that is potentially disrespectful or that the former employee could claim as defamatory, but a complete absence of an explanation can leave employees feeling vulnerable and worried that they could be next. Be aware that employees will be watching your actions and looking for whether they align with your purpose-driven culture and company values.

Conclusion

Although the topic of exiting underperforming employees is not a fun one, it is no less relevant than how to effectively onboard and develop employees when cultivating a purpose-driven culture. Being prepared and sensitized to some of the more common risks and mitigation practices associated with terminating a chronic underperformer’s employment should be on any supervisor’s radar and executives need to have confidence that their company has solid processes to managing these tough situations. Having a clear plan for managing the termination process helps you manage an already difficult situation in a manner that is as respectful as possible to all involved and minimizes the risk of potentially avoidable challenges later.

Managing the exit of chronic underperformers with respect and as much dignity as possible is essential to protecting the purpose-driven culture that you are building. Knowing when to involve the appropriate subject matter expertise is also critical for diminishing your company’s exposure to risk, data leaks, and blemishes to your company’s reputation. Turning a blind eye will erode one of the most powerful assets at your company’s disposal for achieving success: your purpose-driven culture.

Hopefully these events will be rare but remember to exercise grace for yourself and those involved and determine what you learned that will inform how you get better moving forward.

For questions or to find out how EverSparq can help you design any of the tools described in this article or the right fit process for your company, please contact info@eversparq.com

About Christopher Kodama

Dr. Kodama’s 25+ years of executive and clinical leadership encompasses guiding strategy design and implementations for start-ups and new programs, managing IT implementations, and leading cost structure improvement initiatives and turnarounds…