Optimizing mutual benefit by matching skills with need

A dimension of EverSparq’s services includes the ability to subspecialize in healthcare related matters. Recently, the topic of how to successfully recruit and support high-performing physician leaders resurfaced and I wanted to share some of the common patterns, considerations, and themes that I have experienced and encountered over the years as an executive, physician executive, and mentor to new physician leaders.

Physician leaders are highly trained professionals who can bring a unique and important perspective to healthcare business that maximizes the clinical quality and safety of services, engages other medical professionals in the implementation and adoption of change, and enhances the overall value and success of organizations. Over the years, there has been a proliferation of part- and full-time physician leadership roles within organizations ranging from hospitals, medical practices, and integrated healthcare delivery systems to health insurers to the explosion of third-party vendors, all signaling a recognition of the value and importance of having a balanced medical and administrative perspective to be successful in the business of healthcare.

Even with the important contributions physician leaders can bring to a team and company, I repeatedly observe high physician leader turnover, burnout, and dissatisfaction. Looking more closely, patterns emerge of avoidable pitfalls that contribute to these undesirable circumstances including the one-size-fits-all approach to sourcing physician leader talent. Whereas there are numerous studies and articles about physician turnover, there is surprisingly little in the literature on the challenges of recruiting, cultivating, and retaining physician leaders. This article in the EverSparq Healthcare Series explores these challenges and provides insights for those who are thinking about incorporating physician leadership into their operating model, those who are seeking to optimize their existing physician leadership resources and talent, and those who are either considering or already find themselves in physician leadership roles.

What Is Physician Leadership?

Historically, when one thought “physician leader” the typical mold was an individual who could review clinical protocols, medication formularies, advise on clinical quality and patient safety matters, lead hospital medical staff in decision-making related to (re)credentialing new members of the medical staff, and adjudicating physician performance concerns.

These were typically individuals who were elected by their peers to serve in specific governance positions defined by regulatory standards set by entities such as the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services and evaluated by agencies such as the Joint Commission. These were part-time positions that may or may not have been accompanied by a stipend.

Over time, this expanded into non-medical staff positions in which a hospital, medical group, or health system employed a physician in a part- or full-time capacity to help manage an increasing burden of physician-related administrative activities. Concurrently, voluntary medical staff physician leaders were becoming increasingly consumed by managing their own practices and needed to maximize their clinical time to meet patient and financial demands often outweighing the incentives of stipends and the prestige associated with elected medical staff officer positions. Healthcare organizations began to absorb as much physician administrative work as regulatory agencies would allow (independent medical staff and associated physician leadership structures continue to be a regulatory requirement for hospitals).

In academic settings, there was an extensive network of medical specialty departments and divisions with designated physician leads or chairs. These positions often involved providing medical care, leading clinical research, teaching, overseeing the physician activities in the department, and responding to a variety of needs from the overarching administration.

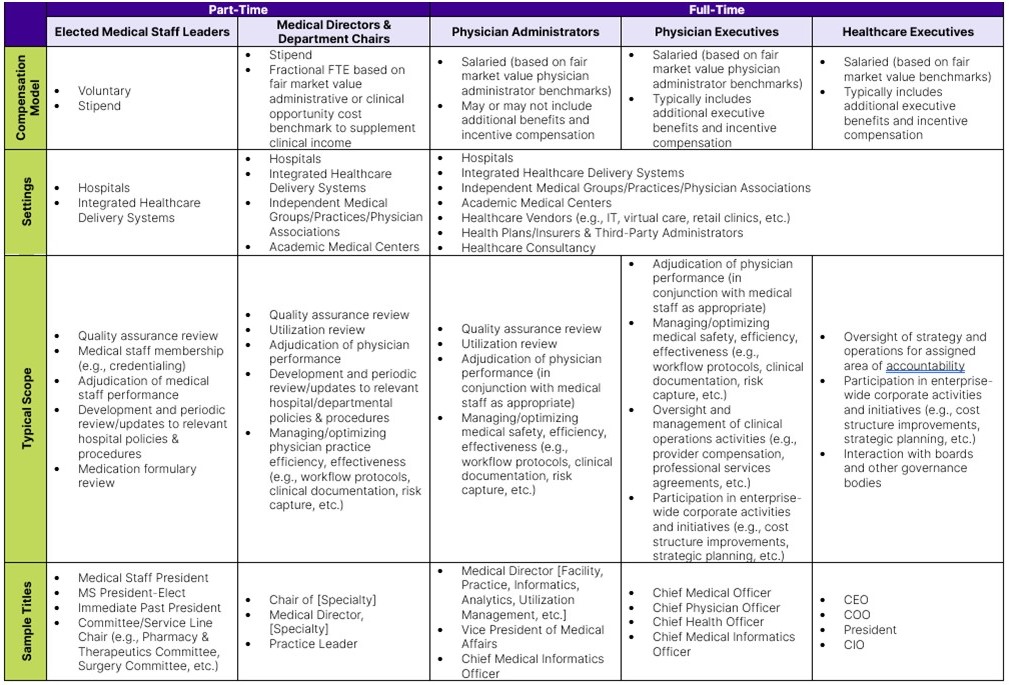

In non-academic settings, physician leaders were often expected to participate in an increasing level of corporate business activities so they could be better positioned to bridge business and medical stakeholder perspectives. As integrated healthcare delivery systems began to increase in number, the proliferation of clinical services and associated health system-employed physician specialties created a degree of physician oversight responsibility that required a growing level of specialty-specific expertise in the form of part-time medical directors similar to the academic department chair model. Although by no means comprehensive, Table 1 provides an overview of physician leadership categories, example titles, scope, and compensation models. The intent of the table is to illustrate the burgeoning diversity of leadership roles that require or can benefit from a physician perspective and the distinct scopes across this landscape that color the requisite level of appropriate leadership and management experience.

Why Is Physician Leadership Important?

When it comes to the delivery of healthcare, the number of considerations and complex interdependencies across various corporate business and clinical dimensions can be overwhelming. No single individual can possibly possess the depth of expertise across the breadth of these dimensions so knowing when and how to add subject matter experts, like a physician leader, to your enterprise is critical.

A physician perspective can be a very powerful asset in a healthcare company. Their years of training and clinical experience can help guide strategy and initiatives in a way that aligns with the practical realities of medical safety requirements and what is considered to be evidence-based, best practice to achieve optimal, affordable clinical quality outcomes. This can create a balance between the business and medical aspects of healthcare that enhances the relevance, credibility, and attractiveness of the care and services being provided to the market. This approach also helps minimize the risk of designing faulty products and services that fail or deliver suboptimal results due to misalignment with medical practice considerations and clinical quality and safety requirements that were either overlooked during the design phase or discovered as late as the implementation and adoption phases. This results in rework and wasted time, money, and resources.

Another key value proposition of physician leadership is the ability of physicians to engage their peers in initiatives that require physician and advanced practicing provider support such as performance improvement activities, electronic health record adoption/optimization, and changes to clinical workflow to name a few. The ability to speak from common experience and navigate the nuances of physician culture can be an accelerator for business success.

How to Configure Your Physician Leadership Strategy

One of the first considerations when incorporating physician leadership into your enterprise or assuming a physician leadership role is to get clear on what problem you are trying to solve and, by extension, how you believe a physician leader perspective will help. As with the design of any operating model, starting with this perspective helps to create clarity on the relevant skills and experience that are being sought.

As described in Table 1, there is a diversity of scope and time requirements associated with physician leadership needs so getting the right alignment is important.

Here are some questions that may help maximize alignment between what you expect and need and who you hire:

- What do you need the physician leader to do?

Consider how a physician perspective can help address the problems and challenges you are trying to solve. Determine the specific duties and responsibilities that need to be covered. - How much time is reasonable to manage the scope of responsibilities?

This is often challenging as it requires synchronizing realistic and sustainable expectations with the imperatives and needs of the company. More on this later, but this is often determined by considering what one can afford, any time-sensitivity regarding specific duties and accomplishment of critical milestones, and the magnitude of scope on a daily, ongoing basis. Can you afford to accommodate a slower pace of deliverables knowing that a part-time role may only involve ½ to a full day of administrative time or is there more that needs to be accomplished in a week that would require a greater percentage of administrative time or even a full-time position? - What can I afford?

As noted earlier, physician leadership can be a hot commodity and there may not be enough hours in the day for a physician to assist, manage, and lead all of the priorities you have in mind. What you want versus what you can afford need to align.

The closer to the part-time end of the physician leadership spectrum, the trickier it can be to devise a fair compensation model that is appealing to candidates and can withstand regulatory muster. Those physician leadership roles that are focused on a particular medical specialty may necessitate a review of the clinical revenue opportunity cost for the physician in question, i.e., what the physician could earn providing clinical care during the time they are expected to spend on administrative activities. This can sometimes be determined by reviewing published physician compensation benchmarks, which have evolved over the past several years to include data sets for specialty-specific physician leadership titles.

Full-time positions often come with additional overhead in the form of benefits and incentive compensation plans, so it is important to make sure those with direct fiduciary accountability for the organization are on board with the investment and clear about the expectations and value of the physician leadership position(s).

(Configuring physician leader compensation models exceeds the scope of this article but can be explored further by contacting info@eversparq.com) - What skills are required to achieve the desired outcomes?

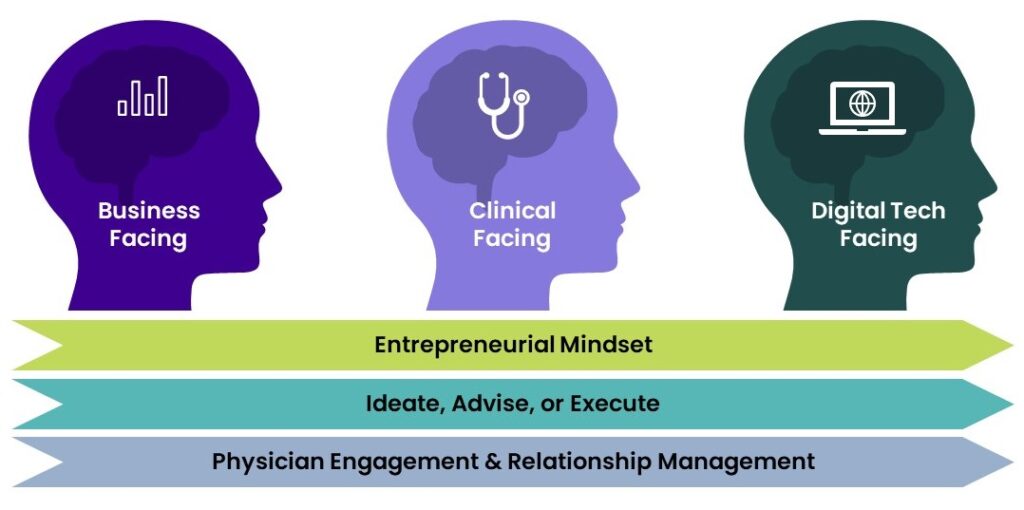

Fifteen years ago, I would have described two “flavors” of physician leader archetypes: business-inclined vs. quality & safety-inclined. With the explosion of healthcare information technology, a new archetype has emerged that I will refer to as digital technology-inclined (Figure 1).

Physician Leader Archetypes

- Business-Facing

These roles typically align more with a physician who has an inclination toward and aptitude for how a company or business is run. This may involve developing strategy, such as creating new business models and identifying, characterizing, and leading growth initiatives and often involves a knowledge of operations and how businesses are run on a day-to-day basis.

- Clinical-Facing

These roles typically align more with a physician who has an inclination toward and aptitude for clinical/medical-related outcomes. Activities may include but are not limited to reviewing performance data to synthesize and identify specific performance improvement focus areas (e.g., clinical documentation, population health management, achieving risk-based contract performance thresholds, quality and safety assurance, utilization review, patient throughput, etc.) and engaging physician colleagues in adoption of new workflows and clinical protocols.

- Digital Technology-Facing

These roles typically align more with a physician who has an inclination toward and aptitude for managing the interface between physician clinical activities and digital technology enablement. This may include managing electronic health record activities (e.g., implementation, optimization, and enhancements), data governance, and/or leveraging healthcare analytics.

Additional Sensibilities

- Entrepreneurial Mindset

Some positions benefit from a more entrepreneurial sensibility like in a start-up company or developing new services and products. This is an important distinction as some physician leadership roles may be more structured, regimented, and rules-based covering responsibilities like utilization review, quality assurance, etc.

- Ability to Ideate, Advise, or Execute

While positions may require all three of these skills, it can be very helpful to be clear about this in job descriptions and with physician leader candidates up front. Some positions, particularly of the part-time variety, may benefit from maximizing a physician leader’s limited time to focus on guidance that only they, with their physician perspective can provide, with other non-physician staff managing non-physician-specific duties. On occasion, a senior level, full-time leadership role may emphasize strategic ideation over execution while others may require a depth of experience and ability to perform both.

- Physician Engagement and Relationship Management

By nature, physician leadership roles involve some degree of direct interaction with physicians and advanced practitioners. However, those physician leadership roles in non-provider industries like insurance and third-party vendors may interact more at the level of physician administrator to physician administrator and less with practicing physicians on the frontline.

Common Pitfalls

The following are common themes that I have observed repeatedly over the years that result in disillusionment of the physician and their employer, physician leader burnout, and, ultimately, turnover resulting in significant disruption and drag on the momentum of achieving company success.

I have also provided tested examples of countermeasures to identify and manage these risks early.

1. Unrealistic Expectations

Healthcare management is not immune to the phenomenon of feeling compelled to boil the ocean. High performing physician leaders often find themselves on the receiving end of an ever-increasing barrage of requests, needs, and other duties as assigned. Depending on the seasoning of the physician, they may not know how to say no (a skill worth developing). I once hired a physician executive to assist with a very specific set of activities only to have them pulled in multiple different directions by other areas of the enterprise. At one point, we realized that because of this scope creep, they were spending approximately 10% of their time performing the duties for which they were originally hired. This relentless intensity and dilution of focus can easily lead to burn out and a degree of dissatisfaction that makes these high performers a flight risk. In addition, their ability to be successful and impactful for the critical priorities over which they are accountable is eroded to the point of incremental gains across an unmanageable breadth of responsibilities.

2. Misaligned Expectations

Referencing the archetypes outlined earlier, I have witnessed the unfortunate circumstance on numerous occasions of one physician archetype being hired into a role designed for a different archetype. For example, with the emergence of the need for business-facing physician leaders, it was very common for a clinical-facing physician leader to be hired into a business role. The physician was labelled as ineffective and often let go when they were actually highly capable individuals mismatched to their role. The company experienced disruption and delays in achieving the goals that this role was supposed to be instrumental in leading and the physicians at large saw this as a cautionary tale for why physician leadership roles were to be avoided.

3. Unsustainable Pacing

I have observed that new physician leaders often hit a wall around 15-18 months into their tenure. I have theorized that this window is related to the way physicians have been trained to practice medicine. In clinical practice, work is typically episodic and time-bound. A diagnosis is made, an order is written, or some other action is taken with a result expected in a somewhat predictable, timely manner.

The pace of healthcare administration is often glacial by comparison due to the complexity of enterprise-wide interdependencies. The actions taken or decisions a physician leader may make today may not manifest as a result for months or years. Compensatory behaviors tend to emerge such as increasing the number of hours and intensity of work to try and accelerate the turnaround time. This seems to be sustainable for about 15-18 months at which point the physician hits a wall, experiencing burnout, extreme frustration, and a self-imposed sense of failure. There may also be collateral impacts to staff if the physician leader expects the same level of unsustainable intensity from them.

Physicians are conditioned to be competitive by nature and put great stock in performing well on the numerous exams required to become a physician and maintain their licenses, their clinical decision-making, the quality of their results, and their ability to address their patients’ needs. When they do not experience the same results in their administrative roles, this can be a significant blow to the psyche. This phenomenon may be exacerbated for part-time medical leaders given the challenges of toggling back and forth between medical and administrative paradigms.

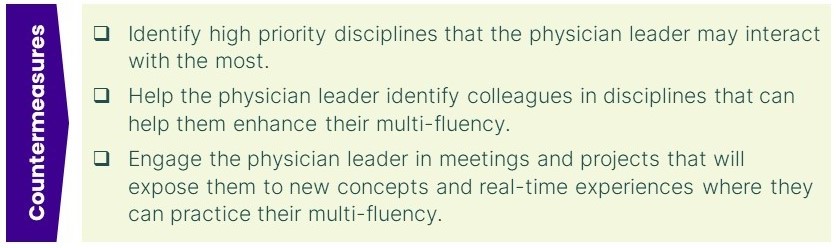

4. Lack of Multi-Fluency

As discussed in other EverSparq articles, multi-fluency is the skill of understanding enough about the terminology, concepts, and cultural nuances of distinct disciplines to effectively translate ideas across these groups. While physicians are well-versed in the scientific language of medicine, it can only be to their advantage to learn the other dialects of healthcare such as finance, information technology, healthcare law, human resources, and operations, to name just a few.

A lack of multi-fluency limits the ability of the physician leader to convey the important medical and clinical perspectives necessary for enhancing overall business decision-making and translate the non-medical into terms that their clinical colleagues can accurately understand and support. Inadequate multi-fluency can also hinder the kind of open design thinking that incorporates the perspectives of key stakeholders and garners the required buy-in to enable successful implementation and adoption.

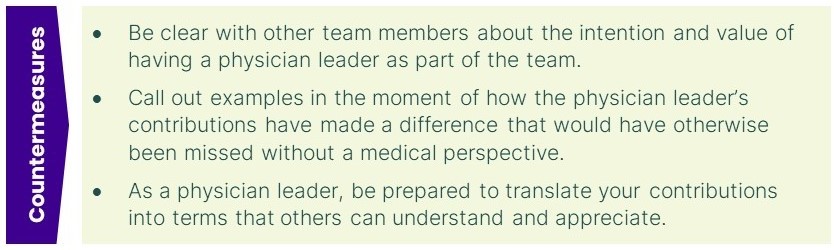

5. Inadequate Positioning for Success

If the value of a physician leader role is not evident to other leaders and team members, there is a much greater risk of non-clinical business leaders dismissing the physician’s contributions and ideas. Multi-fluency can enhance a physician leader’s credibility in the eyes of their non-clinical business colleagues by facilitating accurate understanding and clarity about the value of the physician’s ideas and suggestions. Establishing clear expectations on the purpose and value of the physician leader role and gaining buy-in from contemporaries also positions the new physician leader for success.

Unfortunately, I have seen organizations create physician leadership positions as figureheads with little autonomy or opportunity to truly contribute their expertise to the organization as a leader. As a result, the optics for the value of these positions is opaque and the roles are often vulnerable for being diminished or eliminated during cost structure improvement exercises.

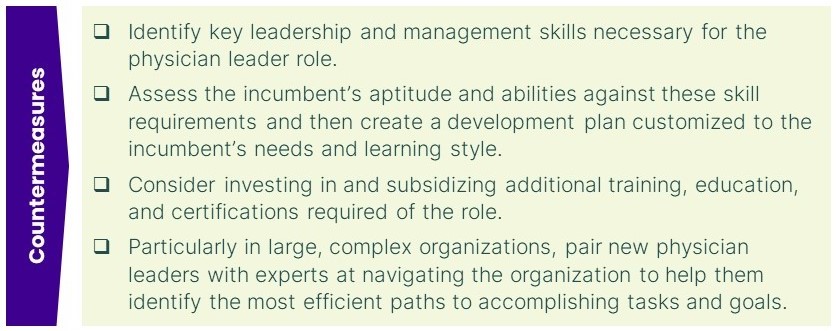

6. Insufficient Administrative Training/Experience

The American medical training system is comprised of a minimum of at least 11 years of formal education (4 years of undergraduate studies – two of which are required pre-medical courses, 4 years of medical school, and at least three years of residency training for a primary care specialty and longer for medical and surgical specialization). And yet little of this training prepares physicians to be successful business leaders.

While not all physician leadership roles require an advanced business degree, there is invariably additional training that can be highly beneficial ranging from building leadership skills such as engaging others in productively navigating change to management capabilities such as understanding financial statements and developing business plans. This additional education and training help enhance multi-fluency and can equip physician leaders with the tools necessary to be successful in what they have been appointed to do.

Conclusion

Physician leadership may provide necessary and highly valuable insights and contributions that will support your company in achieving its strategic goals. This resource can also be difficult to source and requires a significant level of investment which makes it all the more imperative to set your company and the physician leader up for success.

A thoughtful approach to creating clarity and shared understanding among key stakeholders regarding the merits of having a physician leader on the team coupled with ongoing intentional cultivation of physician leader talent will maximize the return on your investment and theirs while supporting the success of your organization.

For questions or to find out how EverSparq can help you design and implement any of the tools or practices described in this article to fit your company needs, please contact info@eversparq.com.

About Christopher Kodama

Dr. Kodama’s 25+ years of executive and clinical leadership encompasses guiding strategy design and implementations for start-ups and new programs, managing IT implementations, and leading cost structure improvement initiatives and turnarounds…