Leaning into challenging conversations with physicians

One of the topics I am often asked about is how to manage disruptive physician behavior. The challenges associated with these critically important discussions and interventions can be especially intimidating when dealing with physicians, but it is necessary to deal with these swiftly and effectively with compassion and respect to build healthy work environments that engage and energize all members of a team or organization.

Physicians are highly trained and skilled individuals often working in incredibly stressful environments and under high stakes conditions where a mistake or error can result in harm or even death. Life is often stressful enough without this amplified pressure. While this does not excuse disruptive physician behavior, it can provide important context for how to navigate some of the nuances unique to managing physician performance compared to non-physician approaches.

While there are some resources specific to physician disruptive behavior available, figuring out how to put them together in a practical intervention plan can be overwhelming. This article is intended to provoke ideas and provide a framework for leaders to piece together these types of plans. We will also look at some common barriers to addressing disruptive physician behavior and how to overcome them along with practical and tactical tips and considerations to help leaders navigate potential landmines to arrive at the most productive outcome possible.

What Is Disruptive Behavior?

Sometimes the term “disruptive” is used in the context of positive change like “disruptive innovation”, “technology disruptors”, etc. This is not one of those contexts. In this case, disruptive behavior is any conduct that upsets others to the extent it interferes with their ability to optimally do their job.

The American Medical Association has integrated specific language in its code of medical ethics describing disruptive behavior as “…speak[ing] or act[ing] in ways that may negatively affect patient care, including conduct that interferes with the individual’s ability to work with other members of the health care team, or for others to work with the physician.” (American Medical Association, 2024).

Ultimately, behaviors that make others feel physically, emotionally, or psychologically unsafe and distract from patient care and the mission, vision, and values of an organization is generally a good rule of thumb when defining disruptive physician behavior.

Why Is It Important to Intervene?

Culture is the cornerstone of how any organization functions. The healthier and more purpose-driven the culture, the greater likelihood of organizational success fueled by highly engaged and motivated employees.

Disruptive behaviors erode purpose-driven culture quickly by creating environments in which others do not feel safe performing their duties or contributing to the goals of the team and organization. This type of context often results in team members devolving into a survivalist, “fight or flight” mentality in which their primary focus, to the detriment of most else, is self-preservation. Physiologically, they are unable to activate the parts of their brain to exercise higher reasoning and engage in effective complex problem-solving. Furthermore, this type of trauma may impact other parts of affected parties’ lives outside of work. The sum is a miserable experience that often results in suboptimal work environments and the expensive situation of employees departing a department or company.

Avoidance of holding disruptive players to account sends a clear message to the organization that treating others with disrespect is acceptable and permissible in your work culture. This can speak as loudly as explicitly stating it in words.

Common impacts of persistent disruptive behavior not specific to physicians are numerous and described in great detail in the literature. However, there are some specific considerations associated with managing physician-specific disruptive behavior including but not be limited to:

Harm to Self and Others

Patient Safety Risk: Staff and patients may fear inciting disruptive behavior from the physician by asking questions or raising concerns. Communication across the entire care team as well as hand-offs of information to and from the physician may suffer. These communication gaps can lead to misunderstandings that result in the very mistakes and errors that the physicians and the care team wish to avoid. Not only is introducing risk of harm to patients antithetical to healthcare from an ethical perspective, there is significant and real financial liability associated with poor patient outcomes.

Unsafe Conditions for Staff: Disruptive behaviors may involve throwing of equipment, biohazardous materials, physical or emotional abuse, and sexual harassment. Not only do these behaviors distract from the main event of safe patient care, they place others in harm’s way and may create liability for the organization.

Risk of Self-Harm: Disruptive behaviors, if left unaddressed can escalate to circumstances in which the physician acutely (e.g., self-injury or suicide) or chronically (e.g., substance abuse) causes self-harm.

Reduced Productivity

Turnover of Staff: The manifestations of many of the conditions above may cause other staff to leave units or departments in which they would interact with a disruptive physician. Similarly, organizations that have a track record of not effectively managing these circumstances are less likely to be viewed as desirable places to work. Replacing and training new staff is expensive and may amplify risk to patient safety and efficiency as the revolving door of new employees, unfamiliar with workflows and ways of efficiently and effectively completing tasks, constantly come and go. This can translate into reduced patient throughput, compromised care coordination, and unsafe discharge planning.

Decreased Engagement: For those who stay, they are more likely to keep their heads down and not “rock the boat”. Or worse, they may adopt similar or complementary disruptive behaviors, expanding the impact of problematic physician behaviors. They may not feel they have any other option than to suffer in silence or to play into the toxicity. These conditions are far from conducive to generating the type of highly motivated and dynamic workforce that generates safe and better quality outcomes and productivity.

Suboptimal Volumes: With all the distractions associated with disruptive behavior, efficiency almost always suffers. Whether it be miscommunication, decreased collaboration and coordination, or the inefficiencies associated with turnover and low morale, patient throughput suffers. Prospective patients will be more likely to seek care elsewhere, and sustainable patient activity will decline.

Common Barriers to Recognizing and Managing Disruptive Behavior

If the impacts of disruptive behavior can be so damaging, why isn’t it acted upon more often or quickly? There are numerous barriers that may, together or separately, contribute to delays in taking action.

1. Unclear Where to Start

Often, the relative infrequency of this degree of disruptive behavior results in leaders not having the experience or knowledge to construct a plan for navigating the various steps involved from an employment and/or legal perspective. Depending on the environment, the complexity of managing disruptive physician behavior can be further compounded by medical staff governance considerations (more on this later). Leaders either put on blinders, hoping that the problem takes care of itself, or proceed in a manner that is even more traumatic and damaging to all involved.

2. Fear of Conflict or Retaliation

The act of confronting disruptive behavior can often conjure hard feelings and anger from the disruptive individual. If they act poorly towards their colleagues, it is unlikely that the leader confronting them for their behavior will be immune. Furthermore, there is often a fear that there will be repercussions like legal action and, in some cases, even physical violence.

If the leader managing the situation is a physician, they may feel that their credibility amongst their peers may be jeopardized depending on how they handle the situation. Furthermore, if they are practicing clinically where they may need to interact with the disruptive physician, they may also feel that this type of confrontation may damage their ability to effectively practice.

I don’t think I’ve ever observed a leader who enjoyed managing disruptive behavior and I’ve always thought that the moment I become numb to the discomfort, it will be time for me to find a different line of work. With that said, there are countermeasures for these risks and, like lancing a boil, sometimes, there will be some pain before things can get better.

3. Fear of Impacts on Physician Staffing

It is not uncommon for there to be fewer physician staff on a team or in a practice than other roles. With physician shortages and competitive hiring dynamics, the notion of potentially needing to exit a disruptive physician poses real impacts on the ability to deliver care. This consideration can generate a perception amongst staff that there will be a double standard for those who might be thought of as indispensable compared to everyone else. But stop and ask yourselves if doing nothing is worth the risk of harm to patients or the loss of staff (including the other physicians on the team).

4. Emotionally Draining & Traumatizing

Similar to what is described above about fear of conflict or retaliation, managing disruptive behavior can be messy. For already oversubscribed leaders, the thought of engaging in a potentially unpleasant confrontation is enough to make anyone want to procrastinate or make excuses that the issue is “not that bad”. Take some time to center yourself prior to the interaction(s) and build time to recover afterwards. As with any traumatic event, it will be important to probe into why you are feeling a particular way about the situation and identify healthy ways to address this.

5. Misplaced Compassion

As noted earlier, physicians are humans, too. Once confronted, they may acknowledge that they regret their actions, but the key is whether they will repeat these behaviors or, even worse, escalate later. As the steps below will outline, while remorse can be a sign that the individual may be ready and able to embrace a change in behavior, it will be important to place the individual on alert that they will need to manage their way out of the hole in which they have placed themselves.

Physician leaders managing these situations may experience a significant amount of cognitive dissonance between their primary professional objective of doing no harm and alleviating pain and discomfort versus meting out accountability that may be upsetting or damaging to the disruptive physician’s career. I have observed a phenomenon in which the physician leader almost rationalizes the disruptive behaviors as “not that big of a deal” because it is so familiar to what they endured during their own training. While that may be true, it doesn’t mean that was healthy, either. To the extent you have access to an appropriate and trusted feedback partner, sound-boarding with that individual may help you discover blind spots in your thinking.

How to Approach Disruptive Behavior

Because it can be challenging and even overwhelming to know where to begin, the following framework is intended to provoke ideas for how to identify and sequence tangible actions as you design an intervention plan.

Start by Mapping Out a Plan

Generally, the following is a reliable checklist to help you begin to organize your thoughts. With that said, every environment has its own unique cultural norms and some will conjure specific considerations that may not be addressed here. The points outlined in this article are intended to help ground you, as a leader, in how you might construct the foundation for how you will manage disruptive physician behavior in a manner that optimizes desired outcomes and attenuates legal risk for you and your organization. Ultimately, you must decide what will work for your style, environment, and circumstances.

Here is an outline of what I have typically thought about when initially collecting my thoughts. Taking a moment to deconstruct the situation into manageable “bites” will make the task ahead less intimidating and much more productive. There are four steps I follow when tackling a disruptive physician behavior situation:

- Evaluate the Situation

- Identify Key Stakeholders

- Plan the Conversation(s)

- Develop an Impact Plan

Key Components of Managing Disruptive Physician Behavior

Let’s take a deeper look at each of the four components to consider when constructing your plan to manage disruptive behavior.

1. Evaluate the Situation

Identify the Disruptive Behavior(s)

Some behaviors are clearly disruptive such as physical assault, throwing things, witnessed verbal abuse, etc. In these cases, even before you conduct your investigation, you need to make a decision about whether to place the offending individual on leave (paid or unpaid) until a proper investigation can be conducted. This can be difficult, particularly if it requires disrupting scheduled patient care, but consider if doing nothing could present real risk of compromise to patient and staff safety. When appropriate, placing an individual on leave will buy you the time you need to proceed thoughtfully and thoroughly.

Subtler presentations of disruptive behavior can be trickier. Consider the series of independent complaints from a variety of staff over a longer period about a physician’s choice of words, mood, or tone. In the absence of documentation, it can be easy to treat each event in isolation rather than seeing the broader impact of chronic disruptive behavior. This lack of continuity can be amplified with turnover in leadership in which the new leader is unaware of the historical track record of a disruptive physician.

Additionally, complaints may be vague and highly charged making it difficult to pinpoint specific troubling behaviors. Some sleuthing will be necessary to characterize and “put your finger on” the specific disruptive behavior(s) in as fair a manner as possible. Even if a complaint may seem minor to you, remember that it made enough of an impression on someone for them to raise the concern, which should be taken seriously.

Here are common methods through which concerns may make their way to you:

Disruptive behavior is any conduct that upsets others to the extent it interferes with their ability to optimally do their job.

Gather the Facts

- Formal Complaints. Sometimes disruptive behaviors and events are shared in the form of a letter of complaint or some organizations may have online reporting systems with a templated form to capture discrete field data as well as comments. All documentation should be saved in a confidential personnel file (and, as appropriate, in a medical staff file system for reasons that will be explained later). Take the time to review and identify predominant behavioral themes, e.g., verbal abuse, unprofessional behavior, etc.

- Comments in Passing. Another common method of surfacing disruptive behaviors may manifest as periodic but consistent negative comments or complaints about a particular individual. It’s important to take this seriously and get to the truth because (i) if there is credence to the allegations, there may be an opportunity to intervene early and (ii) although less common, this could be representative of an evolving instance of defamation with little basis in real disruptive behaviors and should be managed appropriately.

- Observations & Feedback. Depending on your organization’s culture, people may not provide unsolicited feedback without an invitation to do so. Annual evaluations can serve as a default opportunity to solicit feedback and recap your own direct observations to help reinforce positive behaviors, redirect and manage concerning behaviors before they become disruptive, and/or identify disruptive behaviors that have been lurking under the radar.

In the course of a busy schedule, it can be easy as a leader to ignore these signals or put them aside for another time but things rarely just “blow over” and almost always get worse if unchecked. It is important to pay attention and take these signals seriously.

Characterize the Impact

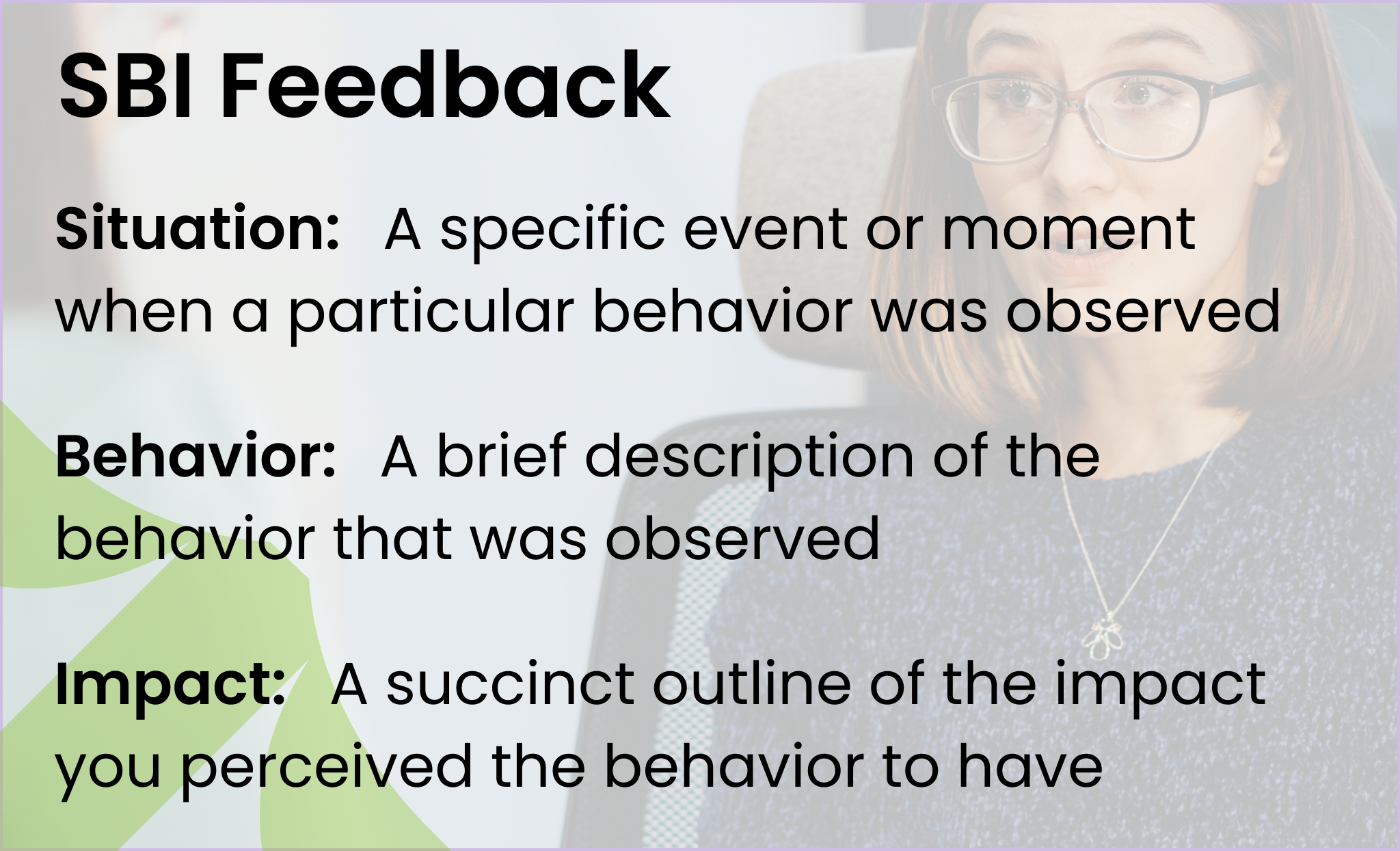

When you become aware of disruptive behavior, gathering specific and concrete examples will help you to start painting a picture of what you are contending with. Deconstructing the examples using the Situation, Behavior, Impact framework (SBI) can be an effective process for organizing your thoughts and identifying if there are patterns and themes of disruptive behaviors common across multiple isolated events. (Check out the EverSparq Insight: Exiting Underperformers with Respect for more information on structuring SBI feedback.) Consider the following examples:

… “Dr. X criticized my decisions and berated me in front of the entire care team. I felt humiliated.”

… “Dr. X told me to stop making suggestions about the patient’s care because they were ‘stupid’.”

…“Dr. X made fun of my appearance and size in front of a patient.”

Rather than treating these in isolation, look for the common theme(s) across all these incidents. When documenting your notes, avoid adverbs and language that is highly subjective – stick to the objective facts as much as possible and avoid judgmental or inflammatory language. Combined with the data you have been gathering, you should be able to describe, with relative objectivity, the disruptive behavior in a compelling way and draw a connection to the impact:

- Situation On three separate occasions, Dr. X publicly spoke negatively about different staff members. (Specific examples should be documented and shared with the disruptive physician as context).

- Behavior(s) Use of disrespectful language; embarrassing others publicly

- Impact Team members are afraid to speak up and contribute to patient care plans. This is resulting in a negative work environment that places patient safety at risk. One team member has already tendered their resignation, citing this treatment as the primary cause.

Determine the Root Cause (or What Isn’t the Cause)

Part of your plan may involve evaluation for potential organic etiologies or factors contributing to the disruptive behavior (e.g., substance abuse, undiagnosed behavioral health issues, metabolic disorders, and even central nervous system disease processes, etc.) Some states have government-subsidized programs specifically designed to assist leaders in navigating disruptive physician behaviors including screening and evaluation for potential medical or behavioral health issues that may be contributing to the problem. These services may also include a limited number of counseling sessions and/or referral to behavioral modification resources, as appropriate.

For example, in Washington State, there is the Washington Physician Health Program (WPHP), which accepts referrals from physicians and/or their employers and assists with evaluation and support planning. In some ways, this functions as a physician-oriented employee assistance program (EAP). If you are unsure if such a resource exists in your state, consider contacting your state medical association or professional licensing agency.

When an organic etiology is ruled out, it may simply mean that the individual’s personality and behavioral attributes are not in alignment with the values and cultural norms of your organization. This may or may not be addressable depending on the degree of personal insight, willingness, or interest of the individual to sustainably modify their behaviors to adequately function in an acceptable manner within your organization.

Right-Size Consequences

When we hear the words “disruptive behavior”, it can be all too easy to jump to the conclusion that the physician needs to be exited from the organization. However, there is a whole spectrum of what constitutes disruptive behavior and the consequences should reasonably suit the infraction. Examples of consequences may include:

- A verbal warning with direct feedback and clear expectations

- A formal written warning

- Performance review evaluation

- A formal performance improvement plan (PIP)

- Involvement of medical staff or medical group governance

- Behavioral modification programs

- Termination of employment and/or hospital privileges

- A formal report to the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB)

2. Identify Key Stakeholders

Another action that will help create clarity and understanding of the steps you may need to take is to create an inventory of individuals or groups of people who have a vested interest in the outcome of whatever intervention you design.

This list will also help you when customizing an appropriate communication plan. Here are some common examples of stakeholder groups – identifying specific points of contact by name for each, will also be useful:

Complainant(s)

Keeping track of the source of a complaint or allegation can help you later when closing the loop with those parties. You may also need to reach out to these individuals to gather more specific information to aid you in your investigation. On occasion, fear of retaliation is so significant that some individuals may submit their concerns anonymously. This speaks to a broader issue of how to repair a group dynamic, culture, or work environment to allow safe space for people to speak openly and candidly – this goes beyond the scope of this article.

Staff

There are staff who fall within the sphere of the disruptive physician who may not have been directly targeted. They are no less impacted by the behaviors and any interventions. These staff may work in a particular hospital or clinic unit, department, or office practice where they either directly interact with the physician in question or are bystanders with indirect contact. Regardless, they will be watching how the situation is handled and draw their own conclusions about how the intervention(s) reflect both your leadership style and the organizational culture you are promoting.

Accountability Bodies

Generally, when thinking about managing a performance issue, one typically defaults to a standard path of human resources (HR) best practices. With physicians, there may be additional steps required depending on the environment in which the disruptive behavior is occurring. When disruptive behaviors are exhibited in a hospital-based setting, the matter of medical staff involvement invariably arises for facilities that are not closed to non-hospital-employed providers (i.e., independently practicing physicians or those who are employed by a third-party medical group or staffing company).

Medical staff is governed independent from hospital administration with responsibility for ensuring physicians (hospital-employed, contracted by the hospital, or independently practicing) comply with evidence-based, best practice standards. Medical staff is often considered accountable for quality/safety while hospital administration manages successful facility operations. With the proliferation of integrated healthcare delivery systems and physician administrators, this line has increasingly blurred.

Medical staff bodies possess their own bylaws, which should be taken into account when navigating the management of disruptive physician behavior. Furthermore, medical staff should have the cover of state-sanctioned protection for investigating quality and safety concerns. In effect, any investigations into physician quality or safety concerns remain protected and non-discoverable to encourage complete candor and comprehensive, unfettered evaluation and to ensure an unbiased investigation. (In Washington State, this is often referred to as a coordinated quality improvement program (CQIP)).

Typically, these days, most medical staff bylaws include guidance on how to adjudicate disruptive physician behavior but even these can be subject to varied interpretation depending on the dynamics of the hospital/medical staff relationship.

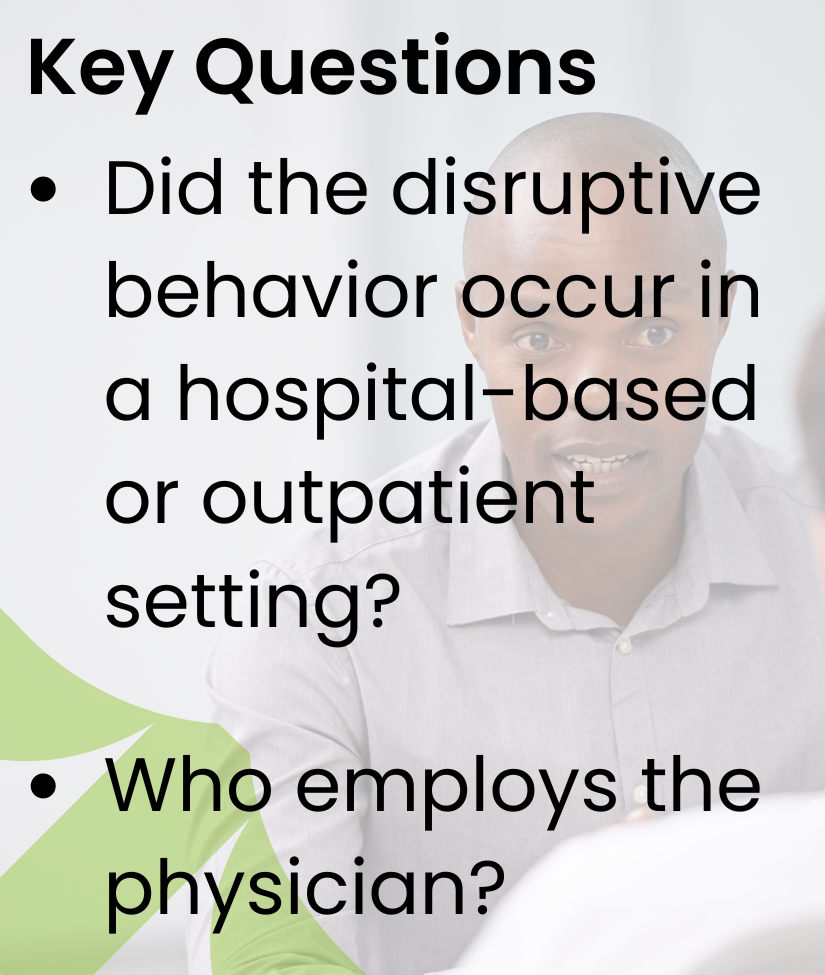

With this in mind, there are two questions that should be answered, initially:

- Did the disruptive behavior occur in a hospital-based or outpatient setting?

This will help you determine whether medical staff involvement is a consideration. - Who employs the physician in question?

This will help you determine which accountable entities need to be involved, who will serve as the point of contact for said entities, and who should take the lead in coordinating the investigation.

Here are some scenarios to illustrate the point:

Scenario 1: Hospital-Based

A surgeon throws medical instruments and biohazardous materials in an operating room that is managed under a hospital license.

Who employs the surgeon?

- The hospital

Depending on your organization’s interpretation of CMS and other regulatory requirements related to medical staff matters, it may be reasonable for the situation to be managed exclusively through the hospital as the employer. However, the dynamics between the hospital and the medical staff and interpretation of certain acute care regulations may dictate that the medical staff governance body (e.g., Medical Executive Committee) may need to be involved in adjudicating the situation. - Independently practicing physician with hospital privileges

These situations are typically managed via a defined medical staff governance process as outlined in pre-existing, codified bylaws. The leader managing the situation may be a hospital administrator in conjunction with the president of the medical staff or, in some environments, this is managed almost exclusively by the elected medical staff president or appropriate delegate. Close coordination with the medical staff office staff, the president of the medical staff, and hospital administration is particularly important in navigating these situations. - A third-party vendor staffing agency or contracted independent medical practice

This is where things can get a bit more opaque. Examples of vendor staffing include locum tenens companies. Contracted independent medical practices may include companies that provide specific types of physician staffing and services (e.g., anesthesiology, hospitalist coverage, etc.)

There are some who would submit that the situation should be adjudicated via the vendor employer adherent to any relevant terms contained within the service contract. In doing so, there is very little, if any, paper trail through the medical staff office.

Others may advocate for adjudicating the situation via the medical staff governance process, which will dictate the consequences for the infraction(s) to the hospital and the third-party vendor. Again, this tends to depend upon the dynamics of the hospital and medical staff as there may not be one clear path. Some things to consider to help you land on a reasonable path under these circumstances may include: (i) the degree of disruption and impact on quality of care and patient/staff safety, (ii) history of prior disruptive behavior (both during their tenure at the facility and potentially prior), and (iii) the risks posed by the absence of any medical staff or hospital administration records if the physician were to leave the organization and exhibit similar behaviors elsewhere, or worse, escalate and cause a major incident.

Scenario 2: Non-Hospital-Based, Health System Owned[1]

A physician in a clinic owned and operated by a health system physically lays hands on a nurse and pushes them because “they were in the way”.

Who employs the physician?

(I have omitted independent practice as it would be rare to find such a physician practicing in a hospital or health system-owned outpatient setting absent some form of a service agreement.)

- The health system

Depending on the maturity of the health system’s medical group, the process typically defaults to a standard set of HR best practices. Some medical groups may have a quality oversight governance body that is essentially an outpatient, non-hospital analogue to the hospital medical staff. It will be important to determine if this type of oversight body exists and if so, how best to coordinate to arrive at a satisfactory resolution. These outpatient-based oversight committees should ideally be protected under a state-sanctioned coordinated quality improvement program. - A third-party vendor staffing agency or contracted independent medical practice

In this situation, the designated clinic site leader would be responsible for working with the third-party agency or contracted practice to adjudicate the circumstances adherent to the terms of the relevant services agreement. Ideally, the contracted entity will have its own state-certified coordinated quality improvement program to enable a thorough and thoughtful investigation.

Scenario 3: Non-Hospital-Based, Independent Practice

A physician in a clinic owned and operated independent of any hospital or health system physically lays hands on a nurse and pushes them because “they were in the way”.

In this circumstance, the physician is part of the practice that owns and/or operates the environment in which the disruptive behavior occurred. In some ways, this is the most straightforward scenario as the designated leader within the practice would manage the situation according to HR standard best practices with the caveat that they may need to consult with general counsel should the outcome of the investigation warrant a report to the National Practitioner Data Bank or similar regulatory body (e.g., CMS).

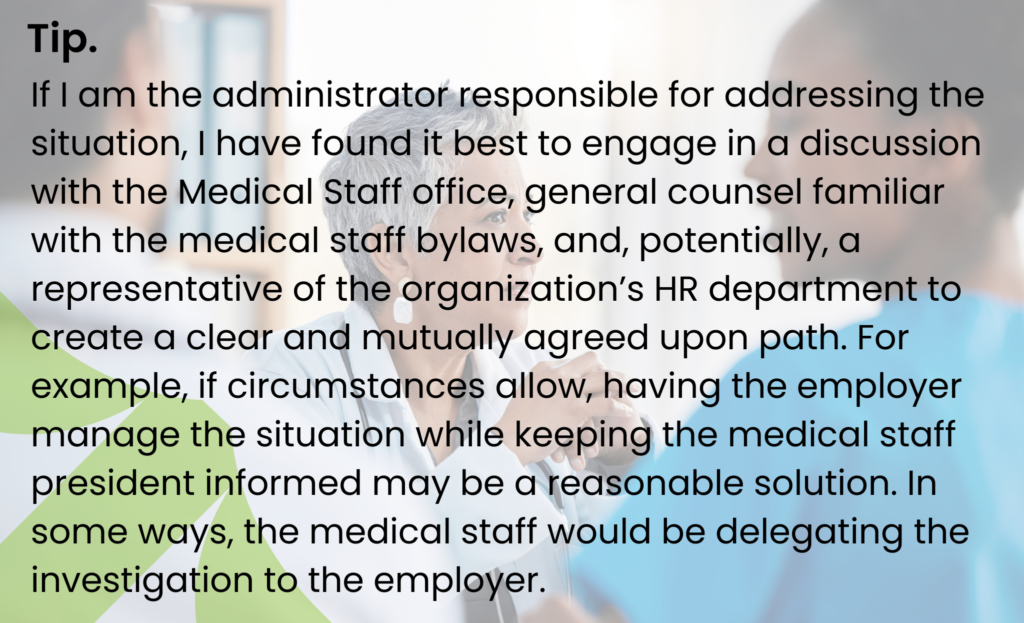

Although identifying the appropriate accountability bodies can be confusing, taking a methodical approach, such as asking the questions above, combined with consulting knowledgeable support resources will often lead to a mutually agreed upon path. Defining this path is important pre-work before proceeding with an investigation.

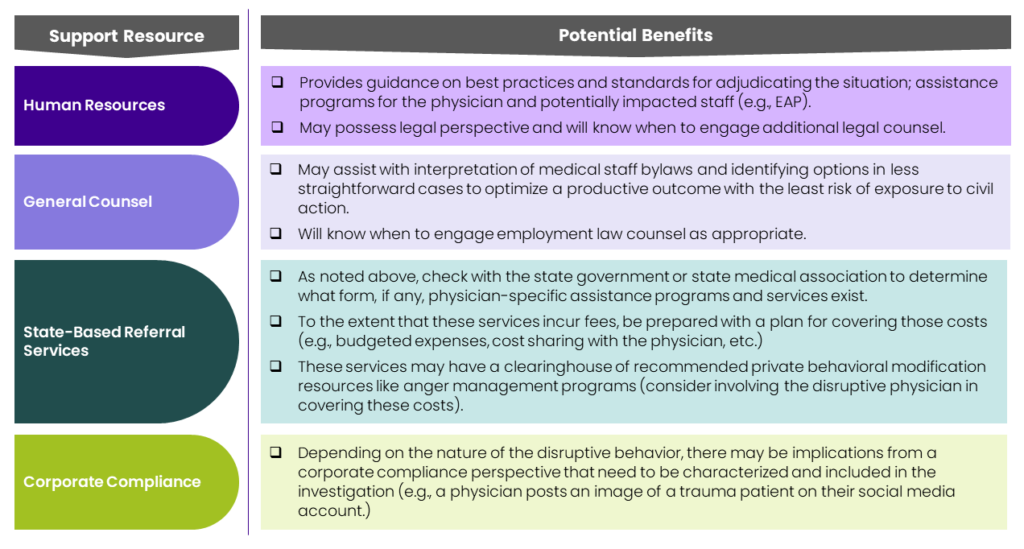

Support Resources

To the extent you have access to certain corporate resources other than those mentioned above, I would highly recommend you engage them. Services potentially most germane are outlined in Table 1:

3. Plan the Conversation(s)

It is likely that you will need to engage the disruptive physician in more than one conversation. While there is nothing wrong with hoping for the best, I find it preferable to be prepared for the worst as this can save time and minimize avoidable unpleasantness.

Here are some steps you may want to take to help get organized:

Form An Agenda and Identify Clear Objectives

The prime objective of the initial meeting should focus on making it clear that there is a problem that needs timely attention. Lay out the problem, facts, and an overview of the process to reach resolution. Close with next steps (e.g., a follow-up meeting to review the progress made by the physician, etc.)

Set Clear Expectations

Throughout the course of the interactions, remain anchored in creating clarity. For those organizations that already have documented behavioral standards (e.g., physician compacts, company values, medical staff policies/procedures, regulatory requirements) that a physician would have been oriented to when they joined the organization, reference these as a standard against which to compare the disruptive behavior. One of the most important messages is to clearly convey performance improvement expectations. If your organization does not have any of these, take this as an opportunity to declare what is or is not considered acceptable behavior (you may want to work with the appropriate organizational stakeholders to codify this for the future).

Be Prepared to Redirect

Soliciting the perspective of the disruptive physician will help round out the picture and may illuminate the individual’s degree of personal insight and situational awareness. There may be a spectrum of potential reactions ranging from acknowledgement and agreement to bargaining, excuses, and denials. Regardless, be prepared to redirect back to the fact that there is a significant enough perception of disruptive behavior to warrant the conversation. Be cautious of falling into the trap of debating the merits of the perceived concerns. Continually come back to what is contributing to the perception and how you can appropriately support the disruptive physician to remedy this.

Clearly Outline Next Steps

As noted above, clarity is extremely important. In addition to verbalizing next steps, clearly document them and provide a copy to the physician to refer to after the conversation as there is a high likelihood that the disruptive physician will be feeling overwhelmed or even may be in a state of shock during the initial conversation. Repetition and consistency of articulating the plan will help normalize what to expect for all involved and leave little room for confusion and miscommunication.

Maintain Objective Documentation

I cannot underscore the importance of this enough. No matter how seemingly inconsequential a performance improvement conversation (even a verbal warning), it will be important to document the facts and any discussion or exchanges in a confidential personnel file and/or medical staff documentation repository. This includes any letters and email exchanges related to the disruptive physician.

Hopefully, the situation you are managing will be a “one-off”, but you cannot know that for certain. A paper trail allows for more troubling, ongoing patterns and themes to be identified and will also assist with continuity as those leaders responsible for managing these situations come and go. Finally, in the event that a situation escalates to threat of or actual civil action, objective and factual documentation will be a key asset for you, your legal and HR colleagues, and the corporate entity you represent.

Include Appropriate Third-Party Witnesses

Depending on the severity of the circumstances, you may wish to ensure that all conversations are witnessed to corroborate statements made during the conversation and to ensure accuracy when filing documentation afterwards.

Be Prepared for Security Concerns as Needed

I wish I could say this isn’t relevant but there have been times in my career in which the disruptive behavior was concerning enough that preparations were needed to ensure the safety of myself and colleagues present during a conversation with a disruptive physician (another example of hope for the best but prepare for the worst). If appropriate, take steps to protect yourself and others in advance. Notify security personnel to be on standby in case things escalate during the meeting and/or if there are concerns about escorting the disruptive physician off the premises afterwards. Always position participants in the meeting space so that there is easy egress.

4. Develop An Impact Plan

As with any plan, it will be important to anticipate potential risks that may result from managing a disruptive physician behavior situation.

The more disruptive the behavior and the more significant the consequences, the greater potential for material impacts of the outcome of an adjudication. The impacts will differ depending on whether the outcome includes the disruptive physician’s departure or if there will be a monitoring period for improved behavior. For less charged or egregious behavior scenarios, impact planning may not be as relevant.

Taking a stepwise approach to impact planning can help prepare you and the team for a smoother landing.

Identify Risks and Impacts

- How will you support staff if the physician is undergoing a period of remediation on the job?

- What will your plan be to manage patient care and business continuity if the disruptive physician is placed on leave or departs the organization?

- What operational steps will need to be taken to off-board the disruptive physician?

- Depending on the circumstances, will there be any terms and conditions associated with a disruptive physician’s departure that need to be considered (e.g., severance, confidentiality agreements, etc.)?

- How will you support remaining staff following a physician exit?

Determine Mitigation Tactics

- Identify an interim staffing solution (e.g., locums, overtime for remaining physicians and staff, adjustment of patient panels, etc.) and plan your timeline accordingly.

- Schedule periodic team huddles to check-in on team morale.

- Organize a predictable method for gathering performance feedback from staff if the physician is engaged in a performance improvement plan.

- Prepare a multi-stakeholder communication plan.

Prepare A Communication Plan

Communication will play a key role in effectively managing a disruptive physician behavior situation and appropriate messages will differ based on audience and circumstances (e.g., if the physician is leaving the organization vs. staying). Referencing the key stakeholder list you prepared previously, determine if communication or follow-up is necessary and coordinate with an HR or legal professional to determine the appropriate level of detail that can or should be shared.

Additional Considerations

Behavioral Modification

In some instances, it may be appropriate for a physician to participate in a formal behavioral modification (b-mod) program such as for anger management or substance abuse recovery. This may be complemented by individual therapy.

These types of interventions should be coupled with some form of organized feedback mechanism from staff on the individual physician’s progress. There are third-party vendor programs designed to provide a comprehensive level of support in these areas.

However, interventions such as behavioral modification programs and professional coaching are only as effective as the individual allows them to be. If the physician is unconvinced that their behaviors are disruptive or that they would benefit from the intervention, they are less likely to engage and internalize the skills necessary to improve. Under these circumstances, the likelihood of success is diminished and the impacts over time tend to be diluted. B-mod programs and coaching are not a panacea and should never be treated as a dumping ground for your problem. These are tools to support you, as the leader, in managing disruptive behavior.

Recidivism

For those situations that result in a sufficient improvement in the physician’s behavior, it will be important to continue to periodically check-in to ensure that the positive modifications are being sustained.

The threshold for intervening will be lower in these instances and may help pre-empt re-escalation. With that said, there may come a time when the disruptive behaviors resurface that it is more appropriate to acknowledge the poor fit and exit the physician. It is important to remember that the individual has already been given a chance – it is theirs to squander.

Is All Unprofessional Behavior Disruptive?

What constitutes unprofessional behavior can be highly subjective.

Consider the physician who is engaging in an extra-marital affair with a staff member on one of the units where the physician works. To the extent that this indiscretion becomes a point of distraction for staff, this could be considered disruptive. There is a fine line between an individual’s personal and professional life choices and it may be a slippery slope to conflate personal views on morality with what is or isn’t considered professional. It may be appropriate to notify the involved parties that how they conduct their personal life choices, while their business, should not manifest in ways that distract others from their work and the focus of safe patient care.

Do Not Underestimate the Importance of Relationship Building

The extent to which you spend time amongst and develop meaningful professional relationships with physicians and frontline professionals and staff will help you build a trust and credibility account that you will benefit from should the need arise to manage disruptive physician behavior.

A healthy, pre-existing relationship may enable greater up-front candor and potentially enhance a smoother process. Although this is not always possible for new administrators who may not yet have had the opportunity to develop these relationships, building a meaningful process for rounding with staff into your calendar will be immensely helpful. To learn more about how to maximize your time getting to know staff, check out the EverSparq article: Valuing & Optimizing What You Already Have.

Conclusion

Managing disruptive physician behavior presents nuances and additional considerations that are not as evident in HR standard best practices. The environment in which the behaviors manifest and physician employment dynamics may make a difference in how you proceed with your investigation and management of the situation.

Ultimately, the goal is to afford a respectful, fair, and equitable process of getting to a productive outcome that protects, preserves, and cultivates a purpose-driven culture in which all team members’ contributions are valued. While the process may be difficult and, at times, unpleasant, taking a methodical approach to teasing apart the situation into manageable components can help.

To recap, the following framework is intended to provoke thought and spark ideas best suited to your circumstances as a leader charged with maintaining a healthy and productive work environment:

- Evaluate the Situation

- Identify the disruptive behavior(s)

- Gather the facts

- Characterize the impact

- Determine any root causes

- Right-size consequences

- Identify Key Stakeholders

- Complainants

- Staff

- Accountability bodies

- Support resources

- Plan the Conversation(s)

- Form an agenda and identify clear objectives

- Set clear expectations

- Be prepared to redirect

- Clearly outline next steps

- Maintain objective documentation

- Include appropriate third-party witnesses

- Be prepared for security concerns as needed

- Develop an Impact Plan

- Identify risks and impacts

- Determine mitigation tactics

- Prepare a communication plan

Remember to take a deep breath and don’t shy away from the challenge believing that it will somehow sort itself out organically – it rarely, if ever, does and typically will make things that much worse later. By leaning in, you have an opportunity to enable safe patient care, support the team (including the disruptive physician), and promote the type of purpose-driven culture that will propel your organization to success.

For questions or to find out how EverSparq can help you design and implement any of the tools or practices described in this article to fit your company needs, please contact info@eversparq.com.

About Christopher Kodama

Dr. Kodama’s 25+ years of executive and clinical leadership encompasses guiding strategy design and implementations for start-ups and new programs, managing IT implementations, and leading cost structure improvement initiatives and turnarounds…

[1] This may be a single owner (the health system) or in conjunction with a physician or other third-party group (e.g., joint venture) in which case, the terms of those agreements will need to be referenced to provide clarity on which entity is responsible for physician performance and the processes for adjudicating this performance.