Cultivating Effective Problem-Solving Skills

A mentor of mine has a favorite question that she asks of those who come to her seeking help with a problem: “What’s your plan?” There is an elegance in how this simple question captures so much meaning: it immediately reminds the other person that they have skills and agency to formulate an opinion on what should be done, it mitigates the temptation for the manager to dive into the weeds and attempt to solve the problem themselves, and it facilitates a much richer dialogue to arrive at a practical solution.

When was the last time you had a direct report come to you with a problem expecting you to solve it for them? Although it can feel good in the moment to solve the problem yourself or provide immediate direction, this can lead to unintentionally limiting others from doing what you have hired them to do. Over time, there is also the risk that others will learn to take the path of least resistance and go straight to you to solve their problems rather than exercising their own critical thinking. This creates a choke point in the decision-making engine of the company and can have an adverse impact on the speed and effectiveness of achieving results.

Although the question frames your expectation that others should not come to you empty-handed when presenting problems, being clear and helping them learn how to anticipate the key components of a viable plan or set of recommendations is a high yield opportunity to coach them to build skill that enhances their effectiveness.

When Is Asking “What’s Your Plan?” Appropriate?

Exercising good judgment is key when asking the question, “what’s your plan?”

Emergency, high stakes situations are typically not the ideal time to cultivate this skill but they can be a good opportunity to role model and debrief later. Conversely, posing this question to simple issues can be misinterpreted as disinterest.

Despite these caveats, there is a fertile expanse of opportunity for when posing the question is entirely appropriate. Understanding the current problem-solving abilities of your employees will color how to manage your expectations and set yourselves up for a productive interaction.

Why Is Asking “What’s Your Plan?” Important?

Asking the question will often provide you with deeper insight into your company’s cultural norms and vulnerabilities that may be preventing employees from maximizing their contributions and exercising the initiative to develop solutions in the first place.

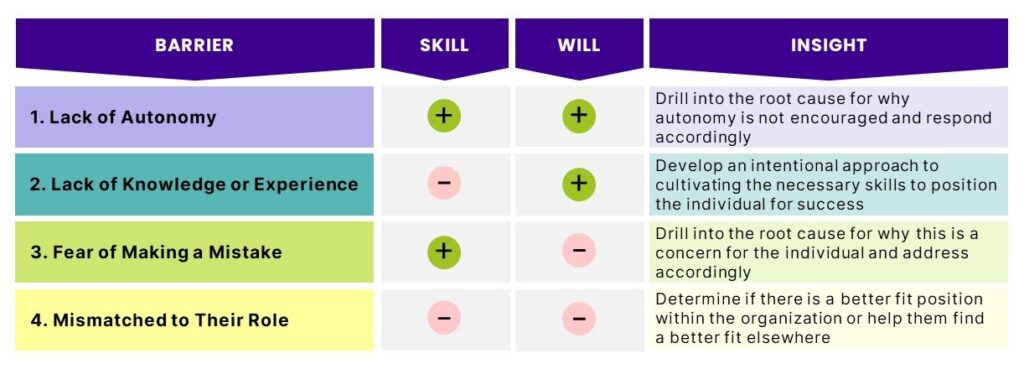

Here are the most common circumstances I have observed for why someone may come to a leader with a problem, empty-handed:

- Lack of Autonomy. The individual possesses the requisite knowledge and is capable of forming and executing a plan with relative independence but may feel hindered by organizational norms such as a culture of micromanagement or centralized command-and-control.

- Lack of Knowledge or Experience. The individual does not know how to effectively form a viable plan but is capable of learning and willing to acquire this knowledge.

- Fear of Making a Mistake. The individual maybe afraid to exercise autonomous judgement for fear of being punished or viewed as incompetent if their plan does not work.

- Mismatched to Their Role. The individual neither possesses the relevant knowledge nor are they interested in learning.

More specifically, there are at least three additional benefits to asking the question:

- Employee Engagement. Typically, people want to feel heard and to make valued contributions to the team or company goals. They were hired into their role for a reason, including their ability to think through problems and develop viable plans. Asking them what their plan is can be empowering and helps foster a culture that invites critical thinking and demonstrates that the opinions of others matter.

- Employee Development. Problem-solving can be an important opportunity to help employees learn more about the business and what skills they can focus on as part of their professional development to be a successful contributor. This also helps build a more sustainable way of doing business as you are teaching and supporting others to share in the responsibility of supporting the success of the company.

- Better Solutions. Often, the person with the problem is far more sensitive to the details and relevant dynamics that are contributing to the issue than you may be as the leader hearing about the problem for the first time. Asking the question “What’s your plan?” increases a sensitivity to the nuances that may matter in determining an appropriate course of action and reduces the risk of jumping to an erroneous solution.

Components of a Strong Plan

When I first start supervising someone, I like to be intentional about discussing our respective “must have’s” for a successful and productive working relationship. One of mine is the expectation that when they come to me with a problem, they do so with some form of a plan or recommendation in mind rather than simply asking me what they should do. It does not need to be perfect but should contain certain key elements that will set us up for a more meaningful dialogue that will point us towards a viable solution that is expected to achieve the objective with minimal damage.

1. Organization & Consistent Structure

I am a proponent of a “tight-loose-tight” management style in which there are certain parameters or processes that are expected as standard practice (tight) yet allow for ample space for individuals to exercise autonomy and self-determination in their daily work (loose). One example of a “tight” process is drafting structured summaries when describing a problem and recommendations to others.

The 4 elements of this type of summary are:

- Situation Describe the situation in 1 – 2 sentences, i.e., what’s the problem?

- Background Succinctly enumerate the handful of most relevant facts and circumstances that are contributing to the situation and why solving the problem matters.

- Assessment Summarize your conclusions about the problem.

- Recommendation(s) State or list the intended actions that constitute the recommended plan.

This particular framework provides insights into how the employee came to their recommendations and makes it easier for you to determine the viability of their plan.

2. Clarity & Brevity

More detail is not always better. In fact, I am more likely to read and absorb a limited set of headers with accompanying bullet-points during the course of a busy day of multiple crises than a single-spaced, multi-page document containing forensic-level detail. Although some problems are complex enough to require a lengthier summary, it will be helpful to communicate your preferences on level of detail to your employee up front. Based on positive as well as constructive feedback, you will be able to calibrate the right level of detail over time.

Whether included in the summary or verbally stated, I also find it helpful to clarify up front what the individual’s intention is by sharing their plan with me. Are they seeking feedback? Are they simply making me aware so I am not caught by surprise? Do they need me to take any action such as removing barriers?

3. Factual & Objective

I have read plenty of summaries fraught with emotional and subjective conjecture, blame for others, and excuses for why there has not been a resolution to a problem. I find this makes it difficult to grasp the relevant details of the situation that will inform a productive solution. It also introduces distracting, unhelpful bias. Sticking to the facts with a level head increases the likelihood that the plan will be viable and understood by others. Though there is much debate on the origins of the aphorism “cooler heads prevail”, this sentiment is very relevant when coming up with a feasible plan.

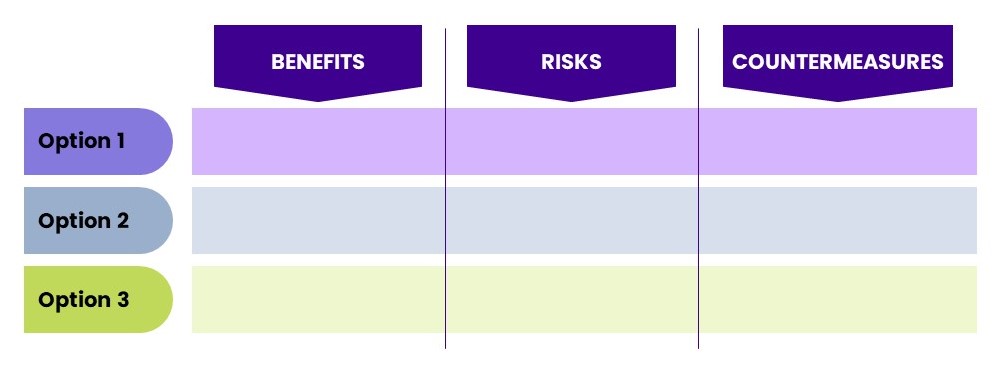

4. Include Recommended Options

At times, there really is only one viable path forward. However, more often than not, there are multiple ways to effectively tackle a problem. If I suspect this is the case, I will outline what I think are the most viable options with a brief description of the respective benefits and risks with countermeasures for each. This can be done in narrative form but if I can create a visual summary table, I tend to opt for the latter to make it easier and more intuitive for the reader (Figure 2).

This demonstrates critical thought while also enabling the decision-maker to choose.

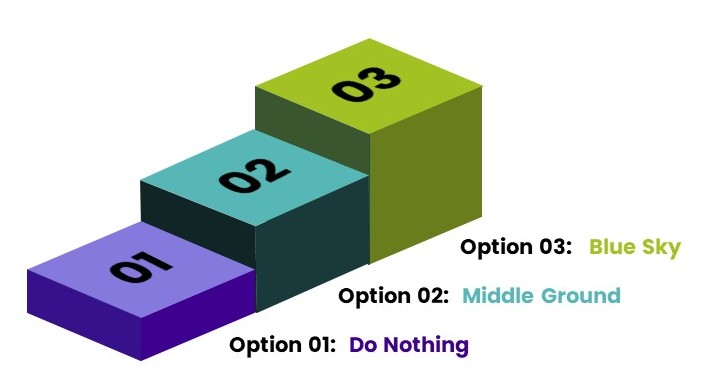

At other times, one may feel at a complete loss about how to proceed. In these circumstances, I recommend defaulting to what I call the “3 Options Technique”:

- The “Do Nothing” Option. Describe what would happen if you did nothing and let the problem or situation ride with minimal intervention.

- The “Blue Sky” Option. This option contemplates a more, if not the most, dramatic possible intervention. Some might describe this as an aspirational plan that is unfettered by resource limitations.

- The “Middle Ground” Option. By characterizing the first two options, you create a more manageable frame of reference comprised of the least to the greatest intensity of effort. I find this makes it much easier to intuit my way to identifying a practical and viable plan.

Some Additional Tips

- Clarify Expectations Early. Depending on the skill level of the employee and the track record that the two of you may have established for working effectively with one another, it is important to be up front and clear about what information will be the most helpful for you in order to support them in developing their plan. If the employee is less familiar or inexperienced with coming up with plans of their own, it can be helpful to schedule a check-in or two to make sure they are on the right track before they present their final recommendation.

- Learn When to Let Go. Even if the employee’s plan may not be how you would have managed the situation, so long as it is reasonably viable, allow them the benefit of learning through doing. This is best reserved for lower stakes situations and can go a long way in demonstrating your trust in and respect for the individual and their abilities. It also provides you with an opportunity to provide positive reinforcement when their plan works or to debrief, learn, and adjust if it does not.

- Adjust Over Time. As you and your employees establish a rhythm with one another, reset the threshold of what types of issues and plans need to be brought to your attention versus managed without your involvement. Through practice, you will develop a sense of what to expect from different individuals and how much trust and autonomy to afford them when it comes to exercising good judgment. Plans that may have come to you for review and comment in the past may shift to periodic briefings on how the deployment of plans is progressing.

Conclusion

Having limited problem-solving bench strength in your organization can create choke points for decision making that jeopardize company success. Conversely, allowing a free-for-all of disconnected plans and solutions creates chaos and slows momentum.

Creating an intentional and measured approach like asking “What’s your plan?” can help you find the sweet spot to engage workforce through appropriately delegated authority and demonstration of trust that will accelerate your company’s progress towards achieving its vision.

To learn more or to find out how EverSparq can help, contact info@eversparq.com.

About Christopher Kodama

Dr. Kodama’s 25+ years of executive and clinical leadership encompasses guiding strategy design and implementations for start-ups and new programs, managing IT implementations, and leading cost structure improvement initiatives and turnarounds…